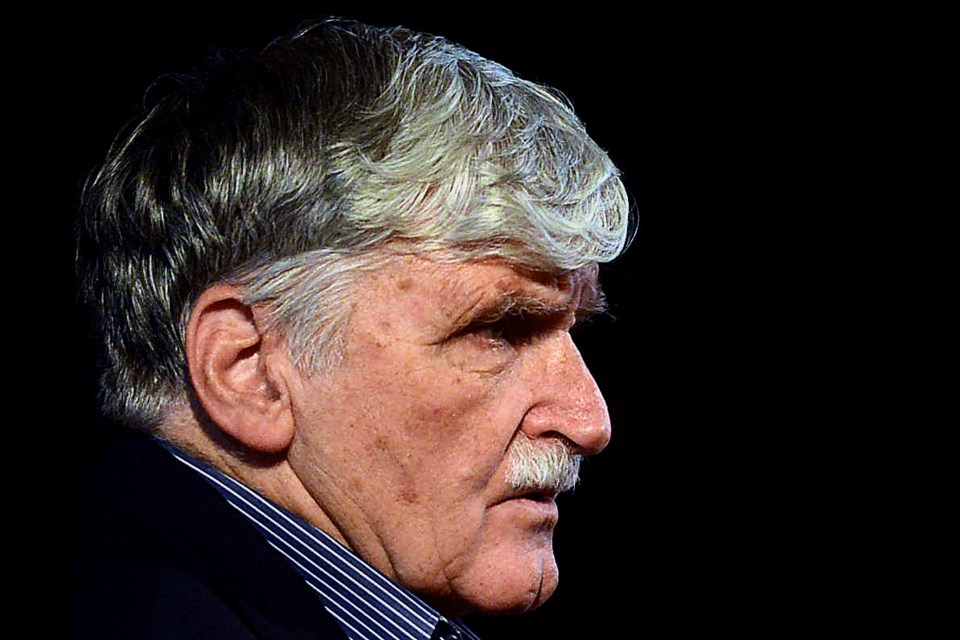

Roméo Dallaire went to hell and back and the devil followed him home.

The retired Canadian lieutenant-general was in charge of the United Nations mission to Rwanda in 1994 when 800,000 people were killed over a 100-day period in an ethnic genocide as the world largely stood by.

That included 350,000 children under the age of 15 killed for no other reason than the ethnic group they were born into.

On Saturday Dallaire, 70, spoke candidly and passionately to a Guelph audience about the post-traumatic stress disorder that haunts him to this day as a result of that experience and of the need for the Canadian government to do more for soldiers and their families who suffer from PTSD.

He opened his talk to roughly 400 people at Hope House by reading a passage his latest book: At First Light: My Ongoing Battle With PTSD.

“Just as I must accept that the Rwanda genocide will never leave me, I now accept that my injury will never heal. For me treatment came too late, the wound was allowed to fester too long, to infect too deeply,” he read.

Any kind of help or advice he sought or was given to him the first few years after the horrors of Rwanda not only didn’t help him, they made things worse.

That “help” primarily consisted of being told “it would go away with time” and that immersing in hard work “would see me through.”

“I am an object lesson on how NOT to treat the returning veterans with PTSD,” he said.

Dallaire still suffers from nightmares and anxiety. He sees a psychologist and a psychiatrist and takes medication to help him deal with his PTSD.

Dallaire said the source of the PTSD suffered by many veterans isn’t so much the experiences incurred in the theatre of conflict, but “repeated assaults on our most sacred fundamentals and beliefs.

“The physical ramifications can be lethal, but PTSD is also a moral injury and ravages our minds, our souls.”

Rwanda was an example that the international community put little value on the people of Rwanda, that those “black lives” did not matter.

Saturday’s event was part of the Café Philosphique author series, a joint event by the University of Guelph, the Eden Mills Writers’ Festival and The Bookshelf. Roughly 400 people attended.

Articulate, poignant, engaging and passionate, Dallaire focused much of his talk on how little is done for soldiers suffering from PTSD and their families.

“What are the tools to prevent them and what are we doing to help the people that do come back injured, and very significantly, how are we doing to help their families who live the missions with them now.”

He said the Canadian government has to “get ahead of the game” by better preparing people to handle conflict and stress and supporting veterans and families for longer periods of time once they return.

“On the 11th of November, where it’s a day to commemorate, we’ll talk about the 158 who died in Afghanistan, we’ll talk about the nearly 15 who died between the Gulf War and Afghanistan, but we won’t talk about the nearly 50 who’ve committed suicide since and that is a scandalous element of irresponsibility,” Dallaire said.

Canada spends billions on weapons but a fraction of that on helping soldiers and their families heal.

Since retiring from the military the Dutch-born Dallaire has been a statesman, senator, public speaker and at the front of worldwide movement to end the use of child soldiers in conflicts around the world. At First Light: My Ongoing Battle With PTSD is his third book.

After reading a passage from his book, Dallaire and U of G history professor Matthew Hayday held a question and answer session on stage.

Dallaire said Canada has a role in a world in chaos.

“We simply can’t stay here and hope that all this is going to pass us by because we have an enormous responsibility as a great nation to in fact engage and offer, as a middle power, our input,” Dallaire said.

“But there are costs. There are costs in money, in sweat, in tears and in blood also.”

“Peacekeeping doesn’t exist any more … we are in an era of ‘peace support operations,” mostly protecting citizens in conflict nations and preventing the killing of innocent people.

“The nature of the beast has changed,” he said.

Questions from the crowd proved very interesting, as those questions included ones from a Canadian Gulf War veteran, a former police officer battling PTSD herself and a young man who survived the Rwandan genocide.