The rate of opioid-related deaths has seen a sharp decline across Ontario in the last year, but things look different in Guelph.

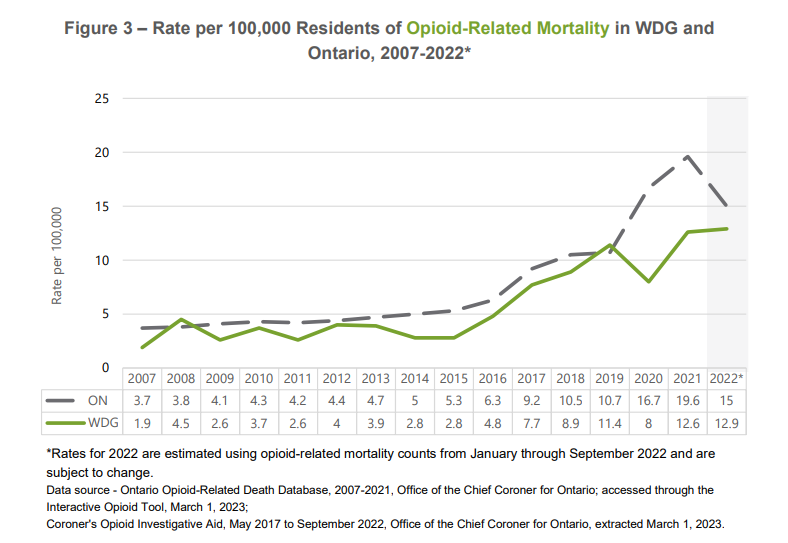

Although Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph was ranked as having one of the lowest rates of opioid-related deaths in Ontario as of November, opioid-related deaths seem to be on the rise according to a recent report from Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health.

The province saw a drop of 23.5 per cent in 2022, while GWD had 31 opioid-related deaths from January 2022 to September 2022, nearly double what it was for the entirety of 2020.

Rates dropped in Guelph in 2020, likely due to increased naloxone distribution and awareness campaign, and the local safe injection site doubling its capacity. But they went back up the following year, and are continuing on that trend.

Since the data is new and preliminary, it’s too early to tell why exactly the province has seen such a sharp decline, while Guelph rates have started to go back up, said Wellington Guelph Drug Strategy manager Adrienne Crowder.

However, she said the pandemic changed the game, because social isolation meant more people were using alone, which increases the risk of overdose.

“Across all of Ontario and Canada we saw the rates go up,” she said.

During this time, the content of unregulated drug supplies also became more contaminated.

“So what people end up using is less predictable and less likely to be what they thought they purchased.”

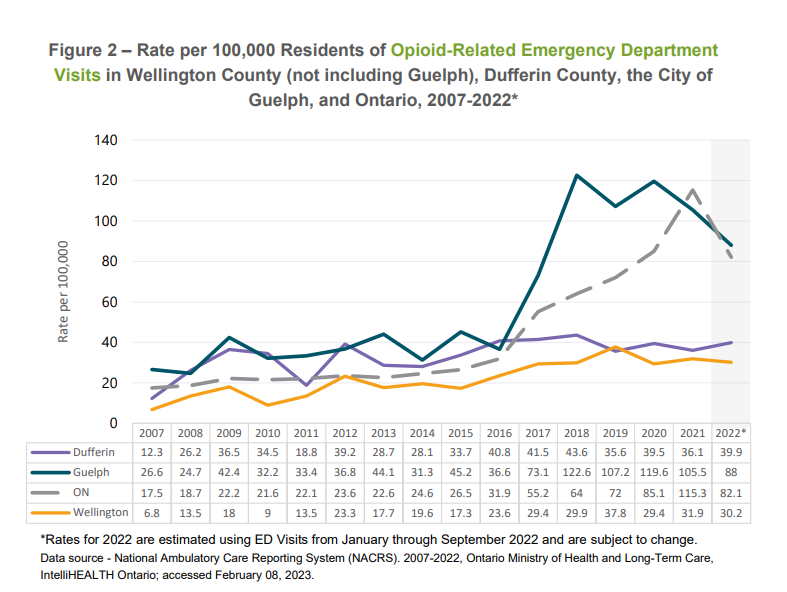

Meanwhile, the rate of emergency department visits has gone down both provincially and in GWD. In Ontario, the rates of emergency department visits went down by 29 per cent in 2022, to 82.1 visits per 100,000 residents compared to 115.3 in 2021.

WDG saw a decline of 11.5 per cent, or 59.3 per 100,000 residents, and has remained below provincial levels since 2019.

However, the decline is so subtle in Guelph that our rates now sit above provincial levels, and 1.2 times higher than that of Wellington County, with rates of 88 per 100,000 residents according to the preliminary numbers in the report.

Still, this decline comes after years of growing outcomes related to opioid use.

“Any reduction in harms related to opioid issues is always a good thing,” said Crowder.

But to put things into perspective, the mortality rate in Guelph and Wellington County is up by 360 per cent since 2015 when the opioid crisis took hold, she said.

Although ER visits are down from the previoius year, she said when looking at the bigger picture, they’re up by 100 per cent in Guelph and 76 per cent in Wellington County since 2015.

“So it's great that it may be less than it was last year. But from a drug strategy, we want those numbers much lower,” she said.

She said emergency visits going down are also not necessarily indicative of fewer drug poisonings, since it can be challenging for people experiencing drug poisonings to go to the hospital, often because of the stigma associated with it.

“And many choose not to go, meaning if it's happening in a setting where there's been no 911 call, they don't go, they get help from friends or whoever's around them. If it is a 911 call, and they pass the basic competency test, they can choose not to be transported to hospital,” she said. “There is a real reluctance to go.”

To get drug poisoning rates back on a downward trajectory and keep them there, she said there is both a short-term and a long-term answer.

The short term is to increase access to consumption and treatment sites and other harm reduction and support services, making sure people using unregulated substances are doing so “as safely as can be.”

Long term, she said the provincial and federal governments need to address the crisis from a policy perspective.

“So things like within Ontario, creating a provincial task force to address opioid issues, collecting data to create a comprehensive strategy, rather than “piecemealing answers community by community,” she said, adding the provincial and federal pandemic response was a good example of what this could look like.

Another component would be making sure people with substance issues get health care responses rather than criminal ones, she said.

“And that requires a change in the stigma with which we've tended to view these issues and our legal response and how we've addressed them,” she said.