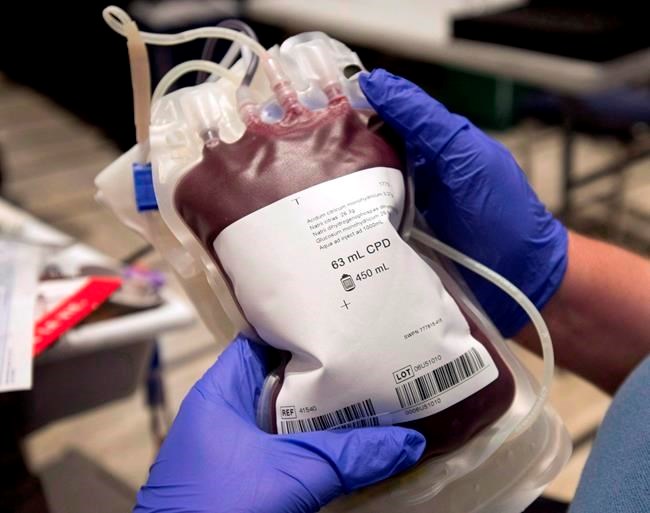

OTTAWA — As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to make people sick across Canada, health authorities are imploring Canadians to donate blood — all Canadians except men who have had recent sex with other men, despite a 2015 Liberal pledge to end this ban.

NDP MP Randall Garrison is among a growing chorus of people saying it's time for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to honour his promises and lift the gay blood ban in Canada.

The policy is discriminatory toward gay and bisexual men and promotes bias against gay men and transgender people, Garrison said.

"The ban actually perpetuates homophobia and transphobia," he said.

"The evidence is everywhere this kind of ban doesn't do anything but stigmatize people like myself who have been in a monogamous relationship for 20 years and not able to donate blood."

The policy of excluding men who have had sex with men from donating blood or plasma — originally a lifetime ban — was implemented in 1992 after thousands of Canadians were infected with HIV and Hepatitis C through tainted blood products.

Donor eligibility criteria has changed since then, including last year when Health Canada approved requests from Canadian Blood Services and Hema-Quebec to decrease the deferral period for men who have sex with men from one year to three months. That is the period they must abstain from sex with other men before they can donate blood.

In the 2015 election that swept him into power, Trudeau pledged to eliminate the gay blood ban. Since then he has committed $3 million for research on moving toward more behaviour-based donation policies.

He once again promised to eliminate the ban in his 2019 election platform, and tasked Health Minister Patty Hajdu with making this happen in her mandate letter delivered last December. No movement has yet been made.

Garrison filed a motion in the House of Commons this week calling on the government to lift the ban, arguing it limits much-needed blood donations in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. It's the second motion on this issue he has tabled. The first was six years ago.

"They've got blood shortages, it's national blood donor week and Canadian Blood Services has been all over the media here in Victoria begging people for donations. And I'm saying, here's one way you can get more donations, you can lift this ban," Garrison said.

In response to the pandemic, Canadian Blood Services has also been encouraging people who have recovered from COVID-19 to donate plasma for a national clinical trial testing the effectiveness of COVID-19 convalescent plasma as a possible treatment for the virus.

The gay blood ban extends to these COVID-19 plasma donations too.

"Researchers are saying there really is a shortage of plasma donations of recovered COVID (patients) and you could increase the supply by lifting the ban," Garrison argues.

Trudeau said Friday he recognizes the need to end the blood donation ban — a policy he says has long been discriminatory.

The changes must be anchored in science, he said, adding much of this scientific research has already been done and hinted at "good things" on the horizon.

"From the very start when we took office, we made significant changes to shorten the wait times but they were still unacceptable. That's why we gave funding to Canadian Blood Services and Hema-Quebec to do the studies necessary to be able to bring in new protocols and we are very hopeful that we'll be able to announce the results and the change very soon."

Nathan Lachowsky, the research director at the Community-Based Research Centre in Vancouver, was among those performing some of the research funded by Ottawa, including looking at some of key evidence gaps that exist when it comes to amending this policy.

This includes looking at how many men in the gay community would actually donate blood if they were eligible and measuring possible levels of undiagnosed HIV infections to determine the likelihood that HIV might enter the blood supply if people are newly allowed to donate.

He also noted many countries around the world have moved to a gender-neutral, behaviour-based assessment of blood donors, including in France where people of any gender who have multiple sexual partners are deferred from donating blood.

"There are good international examples of much better policy that is not discriminatory that we could put in place in Canada, so what we're trying to do as researchers is build that evidence base as much as possible," said Lachowsky, an assistant professor in the School of Public Health and Social Policy at the University of Victoria.

His research centre has released a policy paper with a list of recommendations for government, including a call to adopt a gender-neutral donor screening process, where people are screened the same way regardless of sex assigned at birth, gender identity, gender expression or sexual orientation.

When asked why the gay blood ban remains in place in Canada, Canada's chief public health officer, Dr. Theresa Tam said this week it needs to be looked at on an ongoing basis.

"There needs to be an ongoing examination of science we need to continue to look at this policy," she said during a media briefing in Ottawa.

On its website, Canadian Blood Services says the three-month deferral period came in "as an incremental step" towards changing the criteria.

"Since then, the work continues to evolve eligibility criteria based on the latest scientific evidence, as well as new developments and research into alternative screening methods."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published June 13, 2020.

Teresa Wright, The Canadian Press