Monarch butterflies are born across a vast range of North America that stretches from coast to coast. A broad, coordinated conservation effort is needed protect the declining species, according to new University of Guelph findings.

“Chemical fingerprints” taken from butterfly wings have helped U of G researchers, in collaboration with scientists from a host of institutions, pinpoint the North American birthplaces of monarch butterflies.

The findings, bases on data collected since the 1970s, will play a central role in the preservation of the declining species, according to U of G.

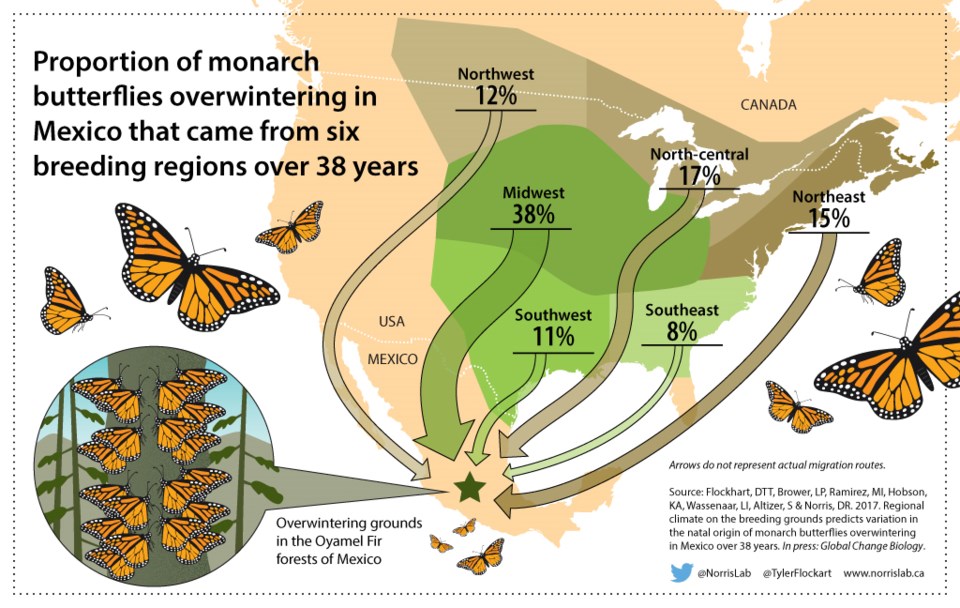

There is now a better understanding of where monarchs originate. A large segment of the iconic butterfly’s numbers come from the US Midwest and migrate to Mexico, as expected.

But it came as a surprise to researchers like U of G postdoctoral fellow Tyler Flockhart that they also have strong roots, or rather wings, throughout Canada and other areas of the US.

It turns out that just 38 per cent of monarchs come from the Midwest. They come from many other places. Protecting the species will require better understanding their many places of origin and protecting them where they live.

The species has suffered a steep decline in recent years, believed to be linked to the destruction of milkweed, which monarchs feed and lay eggs on.

The chemical isotope signatures of 1,000 butterfly samples were analyzed to determine where the individual insects were born. Those birthing locales are widespread, from the northwestern US and the Canadian prairies, all the way across to the northeastern US and the Canadian Maritimes, and down into the south-central and southeastern US.

In a U of G press release, study co-author and integrative biology professor Ryan Norris said conservation efforts must begin immediately throughout North America. The Midwest may be a top-priority for those efforts, but similar work is needed across the species’ range. A coordinated international effort is needed.