Residents of Guelph and other Canadian communities had a special request as Christmas of 1944 approached. They were asked to donate money to pay for food packages to be sent to Canadian prisoners of war being held in camps in German-occupied Europe and Japanese-held territory in the far east.

The Canadian PoWs were men who had been captured at the fall of Hong Kong over Christmas of 1941, airmen who had survived being shot down over Europe, survivors from sunken ships, and troops who had been captured at Dieppe and during the fighting in Italy, France and other parts of Western Europe after the D Day invasion.

Among the Guelph men known to be in German PoW camps were Pte. Stanley Holland of Waterloo Avenue, Brian “Johnny” Downes of Waterloo Ave., William

“Sugar” Kane of Suffolk St., and paratrooper Jack Sinclair of Verney St. Between the time these men had first been reported as missing in action and the time it had been confirmed they were officially listed as prisoners of war, their families had spent agonizing weeks of not knowing if they were dead or alive.

The telegram informing Stanley Holland’s mother he was a prisoner in Germany’s Camp Stalag 7A arrived on her birthday. She said it was the most welcome birthday gift of her life.

PoWs from Western Allied forces held by Germany generally fared better than those held by Japan, whose militaristic government was not a signatory to the terms of the Second Geneva Convention of 1929 which called for humane treatment of prisoners of war.

Father M. Maloney was a Catholic priest who had spent nine months in a Japanese camp in China before he was repatriated to Canada. Speaking to members of the Knights of Columbus at the Church of Our Lady, he described horrific conditions the inmates endured. They were used as slave labour, working 14 hours a day.

They had no medical care. The water was unfit for drinking. The men survived on a diet of horse feed.

Even though conditions for prisoners in occupied Europe were at least marginally better, life in a Nazi prison camp could nonetheless be harsh. A shortage of food was a major problem, especially with the populations of Germany and occupied countries experiencing strict rationing and even starvation.

The food provided for the men in the PoW camps was barely enough to survive on. That was why fundraisers for food drives in communities like Guelph were so important, especially with the approach of Christmas when the men behind enemy wire would most keenly feel the longing for home. For humanitarian reasons, the War Prisoners Aid of the YMCA/YWCA even provided Christmas cards for German prisoners being held in PoW camps in Canada.

Among the organizations that provided aid for Canadian prisoners of war and their families were the Children’s Aid Society, the Navy League, the YMCA/YWCA, the Canadian National Institute for the Blind, the House of Providence, the local Community Chest, Canadian Legion Educational Services, the Salvation Army and the Victorian Order of Nurses.

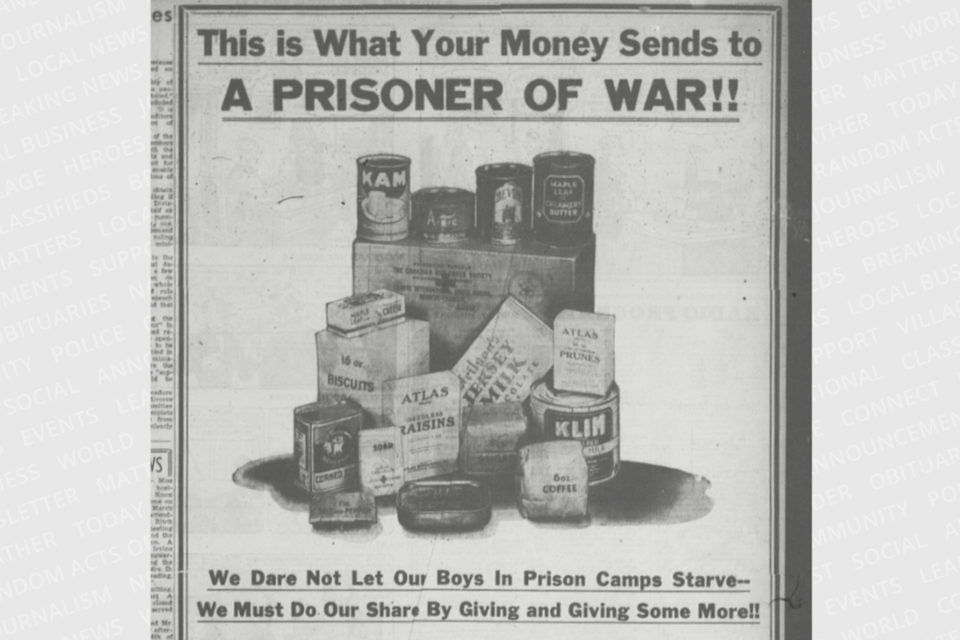

A principal aid provider was the Canadian Red Cross which operated as an arm of the International Red Cross based in Geneva. As shown by an ad that

appeared in the Guelph Mercury, a Red Cross package for a Canadian prisoner of war might include: tins of canned luncheon meat, corned beef (derisively called bully beef), salmon and sardines; tins of butter and powdered milk and a package of cheese; packages of dried prunes and raisins; a 16 ounce package of biscuits, six ounces of coffee, a packet of tea, a bar of chocolate, a package of sugar, a small packet of salt and pepper, orange concentrate and a bar of soap.

By 1944, with more supplies coming from the American Red Cross, special Christmas packages for PoWs could include cans of boned turkey meat, mini-sausages, and deviled ham; as well as strawberry jam, cheddar cheese, plum pudding, assorted candy, mixed nuts, fruit bars, bouillon cubes, dates, canned cherries, honey and chewing gum.

The Red Cross also provided PoWs with cigarettes, books, decks of cards, board games, writing materials, warm clothing, blankets, socks and boots, and items men needed for shaving. Sometimes, in the toe of a hand-knitted sock, a PoW would find a piece of paper with the name and address of the woman who had made it, and an invitation to write to her.

Prisoners used the empty tin cans to make drinking cups and cooking pots, and empty wooden Red Cross boxes to make furniture for their barracks. At Christmas, PoWs would use their raisins, prunes, sugar and whatever other ingredients they could scrounge to make an alcoholic drink they called “jungle juice.”

Cigarettes and chocolate were the currency of the camps, used not only for transactions between PoWs, but between PoWs and the guards. German guards would be severely punished if caught engaging in a camp’s black-market business with prisoners, but a pack of Canadian or British cigarettes could have more buying power than German currency.

The frequency with which Red Cross parcels arrived could depend on which camp a prisoner was held in, and the German officer in charge. Some camp commanders withheld the packages in the expectation of using them as leverage to extract military information from prisoners or convince them to spy on their fellow PoWs. Some guards would pilfer items from the packages before distributing them to the PoWs.

Prisoner escape was a major concern for camp commanders and guards. They would puncture cans of food in Red Cross packages so prisoners couldn’t cache them for use as escape rations. The Germans didn’t know that thanks to a collaboration between playing card and board game manufacturers and Allied Intelligence, there were maps secretly hidden in the cards and German currency in the games, and clips attached to pencils could be used as compasses.

All of this could be of assistance to escaping PoWs.

The Christmas of 1944 would turn out to be the last one men like Holland, Downes, Kane and Sinclair would spend in a PoW camp. They wouldn’t forget those Red Cross packages they received thanks to people in communities like Guelph.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.