The sinking of the British ocean liner Lusitania by a German U-boat during the First World War is one of the best-known maritime tragedies in history, arguably second only to the sinking of RMS Titanic in 1912.

Largely forgotten today is the horrific sinking of yet another British passenger ship. That disaster, so similar to the Lusitania story, had a Guelph connection.

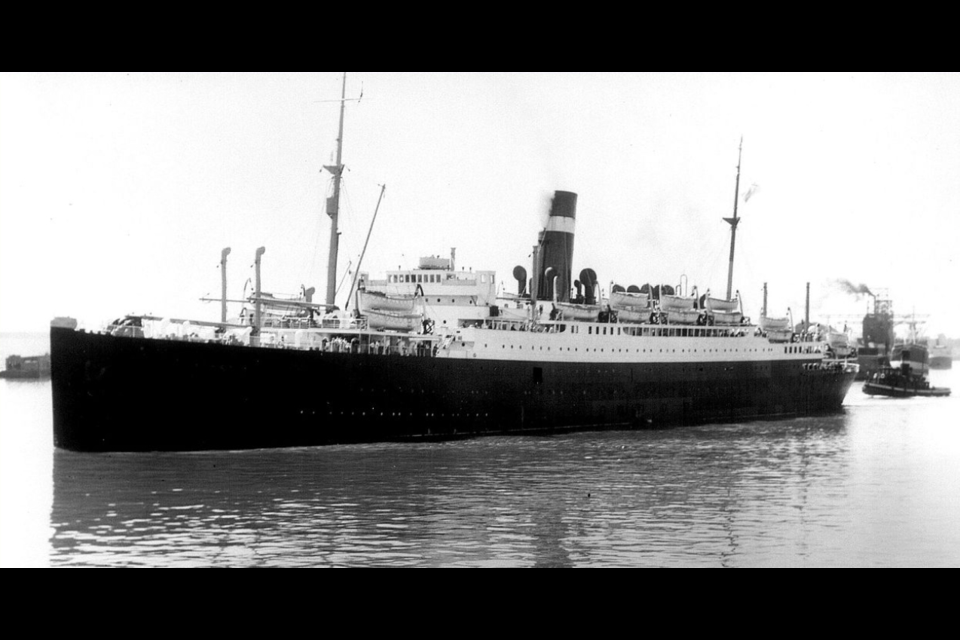

The Athenia was a steam turbine passenger liner, built in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1923. She was named after an earlier passenger ship that had been torpedoed by the Germans in 1917. The name was to prove unlucky.

On September 1, 1939, under the command of Captain James Cook, the Athenia left Glasgow bound for Montreal via Belfast, Liverpool and Quebec City. She had a crew of 315 and carried a cargo of building bricks, Scottish curling rocks, clothing and school textbooks. There were no war materials.

On board were 469 Canadians, 311 Americans, 72 British subjects and about 500 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution. One of the latter, Mrs. E. Meyer, was on her way to a new home in Guelph.

Among the passengers were 12-year-old future hockey star Bill Gadsby, stage and screen actress Judith Evelyn; her fiancé, Andrew Allan, head of CBC Radio Drama; and Allan’s father, William.

One of the other Canadians was Mrs. Mary Agnes Farnworth of Guelph, who was returning from a summer holiday in Europe. Her husband George was the proprietor of Farnworth Florists and Monuments on what was then called The Elora Road (now part of Woolwich Street) across from Woodlawn cemetery. The rest of the Canadians were from across the country, but mostly communities in Ontario: especially Toronto, St. Catharines, Hamilton and London.

The Athenia was not a luxury liner. Her passengers were usually tourists, students and immigrants. For this crossing, there had been a rush of travellers who wanted to get out of the United Kingdom before war with Germany started.

On Sept. 1, Germany invaded Poland, touching off the Second World War. At 1 p.m. on Sept. 2, the Athenia sailed from Liverpool. At 11 a.m. on Sept. 3, the British government declared war on Germany.

U-boats were already lying in ambush in the sea lanes off Great Britain. One of them was U-30, commanded by Oberleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp.

On the evening of Sept. 3, the Athenia was sailing without lights and was following a zig-zag course. Captain Cook was taking standard wartime safety precautions even though he didn’t think there were any German submarines in the area.

Lemp spotted the darkened ship making evasive maneuvers. Hitler had given orders that his naval vessels were not to attack unarmed British passenger ships because he still hoped the British government would back down from actual war. However, Lemp thought the Athenia was an armed merchant cruiser. He ordered two torpedoes to be fired. One missed, but the other one blew a hole in the ship’s port side, killing most of the men in the engine room.

The location of the attack was 200 nautical miles (370 km) northwest of Inishtrahull, Ireland – almost the exact place where the original Athenia had gone down.

It was about 7:40 p.m. when the explosion shook the vessel. Young David Wilcox of Nova Scotia was standing at the prow watching the ship cut through the water when she rose up suddenly and then crashed back down. Many passengers were in the dining room having supper. Mrs. Farnworth was suffering from seasickness and was in bed in her cabin. As she explained later, the cabin “filled with debris, and the lights went out, leaving the place in complete darkness.”

She pulled her coat on over her nightdress, put on her slippers and grabbed her purse. She groped her way through the darkness down a passageway. She met someone with a light who guided her to the companionway that led to the deck. There, a sailor was handing out blankets to frightened passengers.

The Athenia was going down by the stern and was doomed, but the crew fought to keep the ship afloat long enough for everyone to get into lifeboats. Distress signals had been sent and Royal Navy ships were already on their way.

U-30 surfaced and Lemp watched the Athenia sinking. He fired two shells from the sub’s deck gun to hasten the ship’s end. But he didn’t want to be around when British destroyers arrived. U-30 slipped beneath the waves and fled.

The Athenia’s crew managed to launch all of the ship’s 26 lifeboats, although not without difficulty. Women and children went first, so Mrs. Farnworth had a place in one of them. She would spend 12 cold, terrifying hours in the open boat.

The first vessel to respond to the Athenia’s distress signal was the Swedish steam yacht Southern Cross, owned by millionaire Axel Wenner-Gren. Mrs. Farnworth was among the survivors taken aboard.

Soon a Norwegian freighter, the Knute Nelson and an American freighter, the City of Flint arrived and picked up more people. Lives were lost when a lifeboat overturned and when another one accidentally ran into the Knute Nelson’s propeller.

Three British destroyers, HMS Electra, HMS Fame and HMS Escort were on the scene in time to see the Athenia roll over and disappear from sight.

The Southern Cross transferred her survivors to the British warships which took them to Greenock, Scotland. Survivors on the other ships were taken to Galway, Ireland, and Halifax. Mrs. Farnworth sent word to her family in Guelph that she was alive and well, aside from some bruises she’d received from falling debris. She was soon on another ship bound for Canada.

When she arrived back home, she told the Mercury the convoy in which she sailed was stalked by a German U-boat, but British destroyers sank it.

The Athenia sinking cost 112 lives. The youngest Canadian victim was 10-year-old Margaret Hayworth of Hamilton, though she was not the only child who died. Mrs. Meyer survived, but William Allan did not.

The Athenia’s dead were the first casualties of what would be called The Battle of the Atlantic.

Mary Agnes Farnworth of Guelph was a survivor of Canada’s first tragedy of WWII. A CBC video about a reunion of survivors can be seen here.