On the morning of Oct. 7, 1945, after a brief illness, Ellen Jane Jewell of Guelph died in her home on Norfolk Street. According to the obituary in the Mercury, she was in her 75th year, but she may have been about 77.

Jewell was not only a respected member of the community, she was also one of Guelph’s direct connections to the fight against slavery in America.

On one side of her family, she was the granddaughter of a man born into slavery. On the other side, she was the granddaughter of a man who was one of the most important figures in the abolitionist movement – the fight to rid America of slavery.

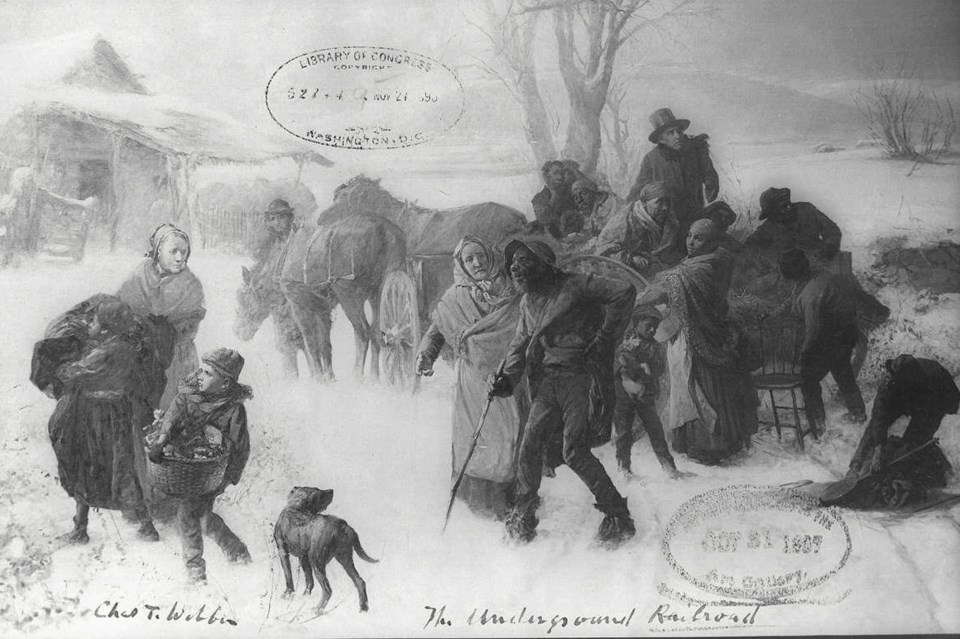

The Mercury obituary said Ellen Jane Jewell’s maternal grandfather was William Still. He was born free in New Jersey in 1821 to former slaves. His mother had fled from a slave owner in Maryland, and his father had purchased his own freedom. Still grew up to become a writer, businessman, historian and civil rights activist. He was a chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Still was also a conductor of the Underground Railroad for a route between Philadelphia and Canada.

Even though Pennsylvania was a Free State, after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, none of the non-slave holding states were safe for people who had fled slavery. The law allowed slave owners to pursue escapees into Northern states and haul them back to the South. Only those who fled all the way to Canada were safe from their former masters and professional “slave-catchers.” Still kept records of all the people he helped reach Canada in order to help re-unite families that had become separated.

Still was called 'The Father of the Underground Railroad.' He sometimes worked with the legendary Harriet Tubman, knew the family of abolitionist firebrand John Brown, and had agents in New Jersey, New York, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New England and Canada. Still was believed to have helped as many as 800 people fleeing bondage reach freedom. He was surprised to find people who were his own blood relatives among those he assisted.

During the American Civil War, Still operated Camp William Penn, a training camp for African American men who wanted to fight in the Union Army. After President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment officially ended slavery in the United States, Still fought against segregation. He was a member of Philadelphia’s Board of Trade, an elder in the Presbyterian Church and founder of the Home for Destitute Colored Children.

By the time of Still’s death in 1902, he had descendants in several states, as well as Canada. A book he had written about the Underground Railroad, based on his own notes from his years as a conductor, became an important primary source for that period of history.

There are differing accounts about Ellen Jane’s paternal grandfather. The Mercury obituary says his name was Henry D. Lawson, who was born a slave in Hagerstown, Maryland. He was made to serve as his master’s coachman. Maryland was one of the slaveholding border states that did not secede from the Union to join the Confederacy at the outbreak of the Civil War, even though much of its slave-owning white population had Confederate sympathies.

The federal government did not initially try to impose abolition in those states. While the Civil War raged, Henry Lawson grew impatient waiting for emancipation to come to Maryland. One day he drove off with a team of his master’s horses. He kept going until he reached Canada.

However, in her book The Queen’s Bush Settlement: Black Pioneers 1839 – 1865, author Linda Brown-Kubisch says his name was Dangerfield Lawson, and he was born in either Maryland or Virginia. In 1842, while fleeing from bondage, he killed his master and then escaped to Canada with the help of abolitionists. He settled first in York County, and then in Peel Township.

Dangerfield Lawson’s oldest son, Henry Dangerfield Lawson, and his wife Sophia, were Ellen Jane’s parents. She was born in Peel Township in 1868 and moved to Guelph when she was 20 years old. She worked in domestic service and then married an Englishman named William Arthur Jewell. As an inter-racial family, the Jewells had to endure the lingering bigotry of an unenlightened age. In that regard, they carried on the struggles of William Still and Dangerfield Lawson.

William predeceased Ellen Jane by 19 years. She supported her family by running a boarding house and a lunch kitchen. At the time of her death, she was survived by a daughter and three sons, one of whom was serving overseas in the Canadian armed forces; and several grandchildren. Ellen Jane Jewell was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.