On Aug. 22, 2017, lightning struck the steeple of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church on Norfolk Street. It started a fire in the Guelph landmark and toppled the iron rooster that had stood vigil atop a church that was built in 1858. In lore and legend, lightning strikes have long been associated with divine wrath, but nobody in Guelph seriously considered the notion that almighty anger might have been behind the bolt from the sky. This was, after all, a church.

Fortunately, the fire didn’t spread beyond the steeple. The damage was repaired and the rooster was soon restored to his lofty perch.

However, just as churches aren’t generally considered likely targets for heavenly thunderbolts, they also aren’t necessarily under divine protection from the ravages of fire, whatever its source might be. Guelph has had a history of church fires, going back to the city’s early days.

Long before the magnificent Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate was built on the high point known as Catholic Hill, a much smaller, more humble Roman Catholic church called St. Patrick’s occupied the site. Guelph founder John Galt, although he was Scottish Presbyterian himself, gave the Catholics the prime spot overlooking the new community out of friendship with Bishop Alexander Macdonnel.

Unfortunately, strife between members of the Orange Lodge and the Catholic parishioners plagued Guelph in those days. On Oct. 9, 1844, news reached Guelph that Daniel O’Connell, a hero in Catholic Ireland, had been released from prison. The Irish Catholic community celebrated the event with a bonfire in the public square. There were mutterings among the Orangemen that there would be a bigger blaze the next night. The following evening, St. Patrick’s, a wooden structure, burned to the ground. In spite of a £50 reward (a substantial sum in those days) offered for information leading to the apprehension of the arsonists, no arrests were ever made.

On the evening of March 16, 1904, Robert Tovell and R.J. Stewart were walking home from work when they saw smoke coming from the basement of Knox Presbyterian Church on Quebec Street. The basement door was locked, but they gained entry by breaking a window. The men found the basement full of smoke and saw that the fire was near the church’s new furnace. Stewart attempted to fight the blaze with a fire extinguisher. Meanwhile, another passerby had seen the smoke and called the fire department from a nearby store.

Stewart extinguished the flames in the basement, but the fire had climbed up inside the walls into the main body of the church. An explosion of hot air blew out the windows on one side of the building. A second explosion took out the windows on the other side.

The fire department responded to the call immediately, but was having problems. Slippery streets meant the hose wagon couldn’t go at top speed. The hook and ladder wagon tried to take a slick corner too fast and tipped over. When the firemen did arrive on the scene went into action, one of the hoses broke. They finally got five streams of water aimed at the fire and put it out. Damage was estimated at $5,000 – about $175,000 in today’s funds. While repairs were made to the church, the congregation held Sunday services in the Guelph Opera House.

In the first week of April, 1907, a series of fires kept Guelph’s fire department busy. The most serious was the blaze that struck the Paisley Street Methodist Church on the sixth. The fire was believed to have started when a strong wind carried sparks from the cupola of the Guelph Stove Company on the adjoining property to the dry shingles of the church roof. Factory workers tried to put out the fire, but their hose didn’t provide a strong enough stream to reach the roof.

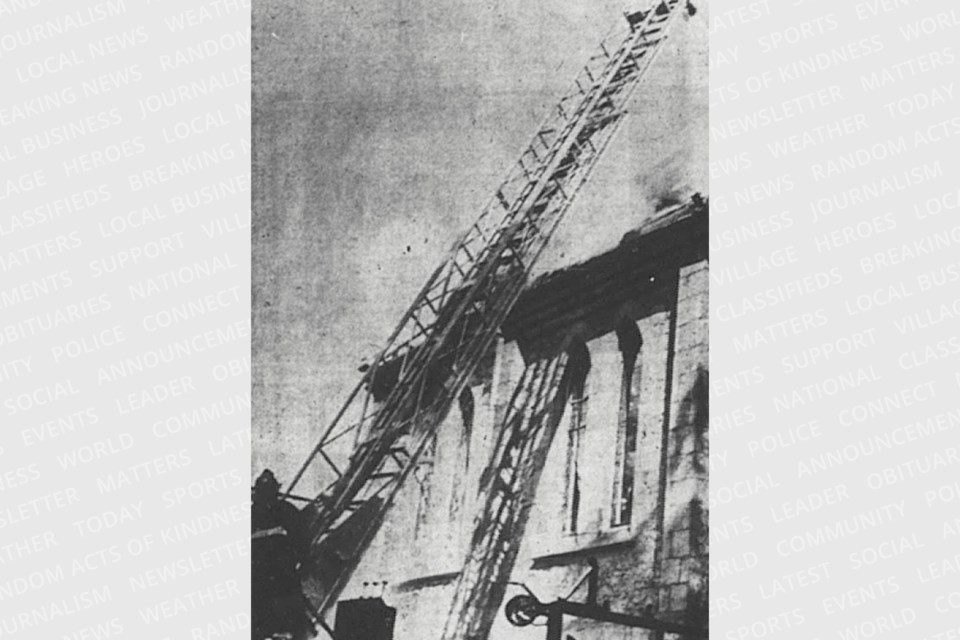

When the firemen arrived, they initially thought the blaze would be easy to extinguish. However, the relentless wind again played a part by blowing the water from the firehoses away from the flames. The firefighters used a ladder to climb up to the roof and direct a stream of water straight at the fire. It appeared to have the desired effect. However, even though the fire on the roof was out, in the attic underneath it was still smouldering. Fanned by the wind that crept in under the shingles, it burst into an inferno.

The firemen cut a hole in the roof so they could aim a hose into the attic. They ran another hose into the church and attacked the fire from below. Volunteers braved the smoke to get the church’s valuable organ and other items outside.

It became clear that the roof could not be saved so the firemen retreated down the ladder before it caved in. The Mercury reported, “But with the crash came the ruination of the interior.” There was nothing the firemen could do now but douse the burning debris. The church was completely gutted. Its congregation now had to find a place to hold Sunday services while contemplating the task of rebuilding.

On the afternoon of May 23, 1963, Norm McKendry of Woolwich Street was the first person to see something was wrong at the First Baptist Church next door. “I was coming down the back stairs and saw smoke and flames coming from a garbage pail at the corner of the church,” he later told the Mercury. “I rushed over to the pail and pulled it away from the building. The window behind the pail was broken, and flames were racing up the shafts just inside. I knew it was too much for me and I called the fire department. They arrived minutes later.”

While firemen battled the flames in the main church structure, volunteers rushed to save items from the Christian education centre at the rear, which had been built just four years earlier. They hauled out curtains, books, chairs and a piano. Rev. Alfred Price saved the church records from his office. Before the firemen could get the blaze under control, the roof collapsed “in a mushroom of black smoke.”

Police kept back the hundreds of people who gathered to watch the fiery spectacle. “I’m an Anglican,” said one bystander, “but it sure makes you sad to see such a fine old church burnt down.”