Guelph’s Brenda Lewis wouldn’t be here today if her dad didn’t escape the Nazis in World War II with the help of a coordinated journey from Prague to London, known as the Kindertransport.

The story about one of the men who helped the mostly Jewish children escape from Czechoslovakia is depicted in the film One Life, currently playing at The Bookshelf Cinema.

His name was Sir Nicholas Winton. He, along with others, safely moved 669 children to England. The children are known as Winton children.

It saw 10,000 children relocated to England from several Nazi-occupied countries.

Brenda's father Henry Lewis, born Heinz Laufer, was 14-years-old when his parents applied for him to be on the Kindertransport.

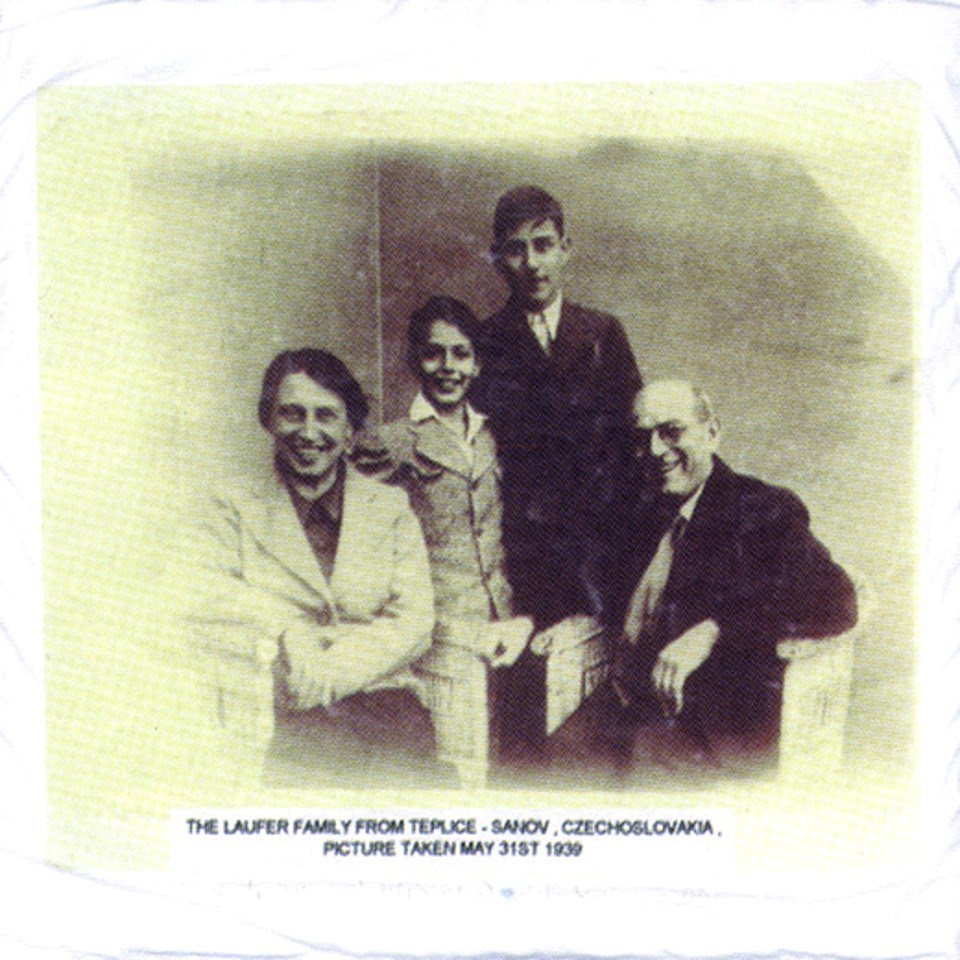

Lewis has a photo of her dad’s family posing together the day before he got on the train. His mother Elsa, died at a concentration camp from tuberculosis. His dad Otto and brother Jiri also died during the Holocaust.

She attended the world premiere of One Life at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in 2023 with descendants of the Winton children.

What happened in the 80s during a BBC interview with Winton was depicted in the movie. The interviewer asked the audience if anyone there was alive today because of him.

During the TIFF premiere Q & A the film’s director asked if anyone in the audience was saved by Winton. Jane Litwack, who is in her 90s, stood up. She was one of the children who survived because of the Kindertransport. The director then asked if there was anyone else who owes their lives to Winton.

About 20 or so descendants of the Winton children stood up. Litwack and the descendants were met with a standing ovation.

“You're not just watching a movie. And I mean for us it's been real, as long as we’d known about it, but for everyone else, they're watching a movie. And yes, they know, it's real, cognitively. But to actually see the descendants” made it quite the moment, said Lewis.

She was part of a Q & A at The Bookshelf’s Sunday Secret Cinema Series where One Life was the film chosen for the screening. The film is showing at The Bookshelf cinema on March 22 until at least the end of the month.

During the film the audience had tears in their eyes and lumps in their throats, said Peter Henderson, cinema manager for The Bookshelf.

He interpreted the film’s title, One Life, to Winton’s outlook “where he has one life to live and whatever he could do, to help and save people was part of his life's mission. Each one of those kids that survived, on their own, is another one life that survives.”

“A story like that invokes deep emotion," said Henderson.

It was great to be a part of because it gave the audience a personal connection to the film “when they actually don't even realize they know someone who's been affected by this,” said Lewis.

The audience asked her questions about her dad and what happened with his family during the war.

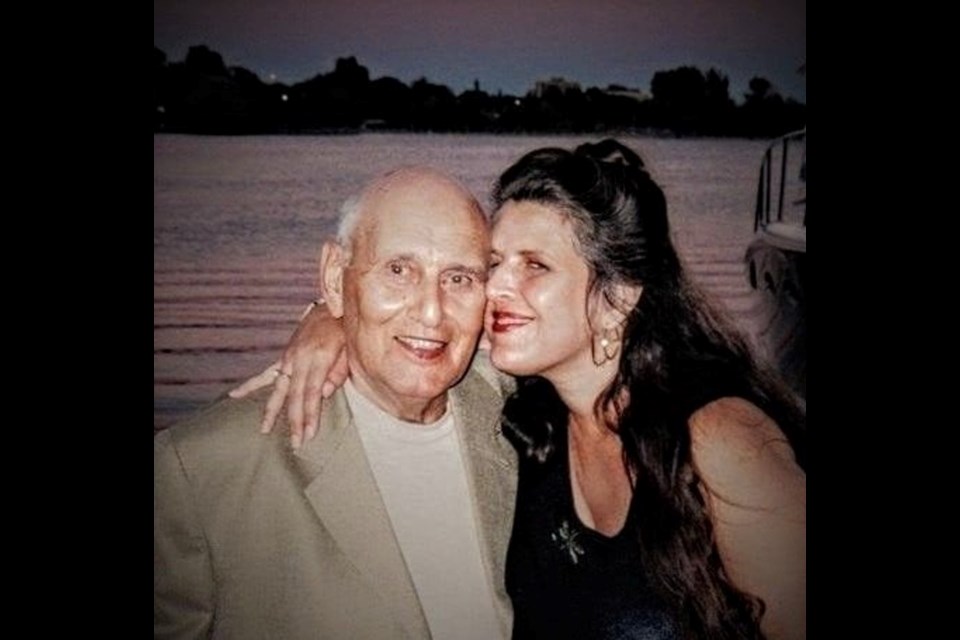

Lewis’ dad died at 84 in 2007. To honour his legacy she lives by his ethos of paying it forward.

She believes if something good was done for you, especially in a tragic situation, it falls on you to also do something good in the world and help others.

Lewis is still connected with some of the Winton children’s descendants. In 2009, she went to Europe to be part of a commemorative re-enactment of the Kindertransport journey. In London, the last stop of the train at Liverpool station, she met Winton.

It was an emotional moment for her.

Lewis said her dad believed he was chosen to be part of the Kindertransport because he spoke English. His parents had him take piano lessons and to get out of taking the lessons he suggested he take English lessons instead.

After the Kindertransport journey he ended up in the English countryside with other children where they lived in dorms. It was set up like a school where they would learn academically and also learn agricultural skills.

He would receive letters from his parents but the letters stopped.

He and his wife were both in the British army and met after the war ended. They started a life in Canada likely because they thought it was a safer place to raise a family.

Lewis’ dad went back home but it wasn’t the same. One of the family's properties was returned to him but it was in bad condition so he sold it. Her dad, like many others, tried to get reparations, she said.

He worked at RCA Victor in Montreal and became a respected union leader. He moved to Prescott when a plant opened there. Even in his retirement people still called him for advice.

“He was just so respected and really loved as a person. He was a very kind person. He was very strong and solid, but you know, he was warm,” said Lewis.

Her dad and mom were involved in social justice. “They were gentle people, but real rabble rousers," she said. They were open to talk about the war with their family.

In her late 20s Lewis visited the concentration camp where her grandmother died. It was one of the hardest things she had ever done. She has outlived her grandmother by quite a few years which is why you won’t hear Lewis complain about getting older.

It’s a privilege to get to live her life without having to face tragedy like her family before her, had to endure.

Lewis emphasized it wasn’t only Winton who helped save the children but others who helped coordinate the journey.

Her dad’s and the other Winton children’s stories are ones of resilience.

“I think it's a story for our times, because unfortunately, humanity's inhumanity to humans hasn't stopped,” she said.

"Amidst all the pain and suffering and the horrors of war, when someone survives, their survival story is a glimmer of hope for others," said Henderson.

There are people who can give a glimmer of hope “and you can be that person, however you can," said Lewis.