On Christmas Day, 1958, five people were shot to death in a cabin in the little Northern Ontario community of Ear Falls, 120 kilometres north of Kenora. Then, on Dec. 27, Guelph became a principal scene in a case of murder-suicide that claimed four lives.

The two crimes were not connected, but together they made that holiday season one of the most horrific weeks in Ontario history.

The central figure in the Guelph tragedy was Harold Reynolds, age 57, who resided in Greensville, near Hamilton. Life had dealt Reynolds some cruel blows. Two years earlier, his son had been killed in a logging accident in British Columbia. Then his daughter, a mother of four, had been killed in a car accident at Dryden.

Reynolds had invested money in a lumber business in British Columbia. When it failed, he’d moved with his wife Suzie and their three-year-old granddaughter Donna into the basement apartment of a house in Greensville that was owned by his step-sister, Maud Grisch. Maud’s parents had adopted Reynolds when he was nine months old, and he and Maud had grown up together.

Soon after the Reynolds family moved in with her, Grisch sold another house she owned in Dundas. Also involved in the real estate transaction was her cousin Mary “Jo” McQuinn, who lived in Guelph with her husband Ambrose (or Ambrois), a painter employed by the Ontario Agricultural College.

Reynolds had been unemployed since the failure of his business. Since the deaths of his son and daughter, he’d been moody and argumentative. Now he felt he was owed a share of the money from the sale of the house. Grisch didn’t agree, and the two quarrelled. A boarder named James Nelles witnessed the fights that went on over a period of weeks.

On the evening of the 27th, Reynolds gave Suzie sleeping pills and put her to bed. Then he went upstairs and confronted his step-sister once again about the money. The argument became heated, and Reynolds struck Grisch. She fled into her bedroom. He ran downstairs to his apartment. When he came back up, he had a .38 automatic pistol.

Nelles tried to stop Reynolds. He grappled with him, but the much bigger Reynolds threw him aside. Before Nelles could recover, Reynolds strode into Maud’s bedroom and fired twice. Maud Grisch, age 66, was dead with a bullet in her head and another in her chest. Downstairs, little Donna heard the gunshots but Suzie was sound asleep.

Reynolds ran out of the house, jumped into Maud’s 1947 Plymouth and headed for Guelph. Nelles phoned the Ontario Provincial Police station in Dundas. Soon the OPP put out an all-car alert for the armed suspect.

Shortly before midnight, Ambrose and Jo McQuinn, ages 51 and 53 respectively, were sitting down to a buffet dinner in the dining room of their home on Summit Cres. in Guelph. With them that night as dinner guests were two old friends, Joseph Carr of Alberton and Caroline Addison of Hamilton. When there was a knock at the kitchen door, Ambrose went to answer it. He came back into the living room and said, “Jo, Harold Reynolds is here.”

Mrs. McQuinn got up from the table and went into the kitchen to see what Reynolds wanted.

Her husband followed. Then Carr and Addison heard several shots.

“All we heard were some noises like ‘pop, pop,’” Addison said later. “And then there was silence.”

The two hurried into the kitchen where they saw the McQuinns on the floor, Jo sprawled over Ambrose. They called for the police and an ambulance, but the McQuinns were dead. Jo had been shot once in the chest, and Ambrose twice in the chest and once in the neck. Neither of the guests saw Reynolds, who had dashed out of the house immediately after the shooting, but they’d heard Ambrose say his name.

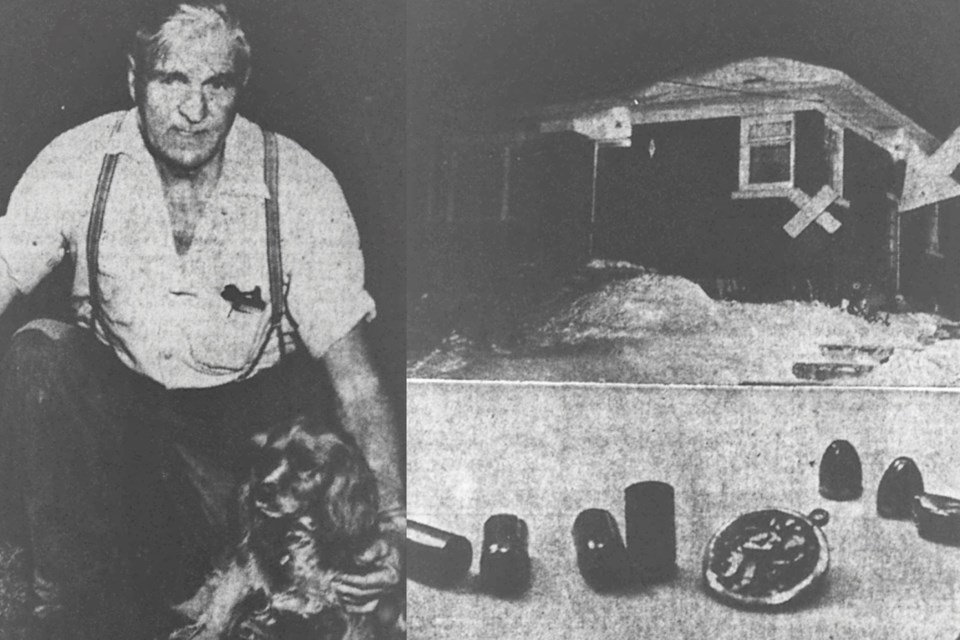

Deputy Chief Robert Gill of the Guelph Police Department quickly arrived at the house along with Det. Robert McCarron and Const. Joseph Clark. They found the shoulder of Jo’s blouse was ripped, indicating that Reynolds had grabbed her and shot her at point-blank range. Steel-jacketed bullets had passed through both victims’ bodies and struck the stove and a cooking pot. One bullet had been deflected by a St. Christopher medal Ambrose wore around his neck.

None of the McQuinns’ neighbours heard a thing. It wasn’t until the Guelph police issued a general alarm for officers to be on the lookout for Reynolds that they learned of the murder of Maude Grisch and realized the slayings were connected.

After killing the McQuinns, Reynolds drove at high speed down Brock Road toward Dundas. He was spotted by OPP officers who gave chase. About half a mile from the house where he had murdered his step-sister, Reynolds pulled off the road. Police cars screeched to a stop, three officers got out and approached the Plymouth with guns drawn.

When they reached the vehicle, they saw Reynolds slumped over in the front seat. He had shot himself in the head. The police rushed him to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Hamilton, but he died in the emergency room.

When detectives searched Reynolds’ apartment, they learned the night’s mayhem had been pre-meditated. Reynolds had left suicide notes. In his last message to his wife, he’d written about his resentment of the way his family had treated him.

“I’m going to settle this once and for all,” he said. “I’m sorry this had to happen, but this was the way it was.”

In a note to the police, Reynolds said, “This is a little bit of justice, the hard way, for there most certainly is none under this phony system called democracy with the phony Bible-packing hypocrites.”

A coroner’s jury concluded that Reynolds had been mentally depressed and “had reason to be deranged.”