I’ve never been very good with walls. I just can’t seem to take ownership of them. I leave walls to those who aren’t afraid to make them their own.

I got my first set of walls when I was about 12-years-old. It was a big deal and a big responsibility. I dropped the ball on those walls.

What you do with your first blank wall can determine the course your life will take when confronted by a wall. I got off to a bad start and never fully recovered.

The higher-ups in the social order of my family had the privilege and power to claim and adorn walls, but not me. My mother was the ruler of walls in the house.

She could put anything on them she pleased – souvenir spoon collections, embroidered art, knife sets, mirrors, photographic collages.

I was the youngest, at least for eight years, in a family of six children, and so I was at the bottom of the wall hierarchy, subordinate to the older ones who had earned the right to place emblems of personality on walls.

They could, if so moved, place a poster of Janis Joplin on a wall, or a painting done in a high school art class. They could affix a wooden shelf to a wall and neatly arrange it with special books and Montreal Canadians hockey cards. They could decorate an entire wall with a series of favourite record album jackets, if that was the wall statement they needed to make.

We had a tiny house. Wall space was limited. If you owned some, you were a somebody.

Through a kind of granular convection process that moves the larger, older bodies up and out of families, walls in our little farmhouse eventually opened up to me. Space became available for me to use as a blank canvas for my young and undeveloped identity.

The walls of a small upstairs room I had long shared with a brother 14-months older than me became mine to explore when the brother moved to the bunkhouse. He essentially had his very own shack tucked away in the corner of the farmyard, with a wood-burning stove, two rooms, and more walls than he knew what to do with.

At the age of 12, I had many interests. I liked drawing and painting. I loved maps, especially very old ones. I had an interest in Aboriginal history and in Metis culture. I liked the Viking explorers and often played one of them on my spring rafting expeditions.

But none of these interests seemed to come to the forefront when it came to the ambitious and unnerving project of decorating my first wall.

As a flat and expansive receptacle, a wall is thick with potential for independent self-expression. But, like a billboard, that surface can also be used as an advertisement, a sales pitch, a way to attract others to your brand and win their approval.

My father had been a gifted athlete, a hockey and baseball player. Two of my older brothers were gifted at hockey and baseball. I was gifted, but not quite so much as they, in hockey and baseball.

I wanted the same prestige those older ones enjoyed as successful athletes, but I was always small for my age, and small does not always translate into athletic reputation.

For my first wall I succumbed to my insecurities and I went with a loud baseball theme. I neatly cut out a dozen or more pictures from Sports Illustrated, Baseball Digest, even Life magazine, and taped them to a wall in an aesthetically pleasing manner.

In the selection of the pictures, I now realize, were hidden the character traits I wished for myself. The clumsy artistry of Brooks Robinson, the rebelliousness of Doc Ellis, the cool of Joe Pepitone, the masculinity of Reggie Jackson.

That baseball-themed collage stayed on that bedroom wall for well over 15 years. The colours faded, the paper became brittle, and the tape lifted. It had staying power as a montage of the characteristics I wanted to possess and wanted others in my family to recognize in me.

Looking around the walls in my office space at home, I can report that the predominant decorative element is currently a series of four baseball gloves occupying one corner.

I really must change my relationship to walls.

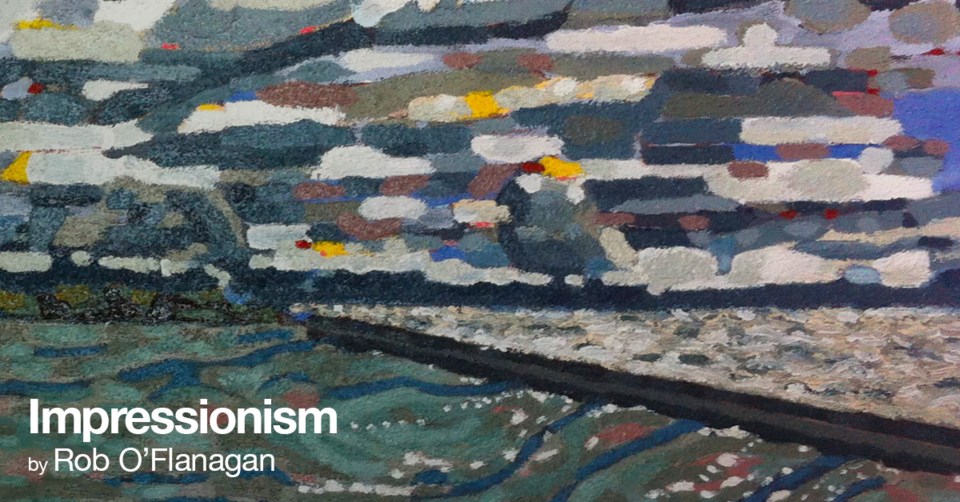

Impressionism with Rob O'Flanagan will be published every Wednesday on GuelphToday.com.