If you sent me a plain brown envelope a few years ago, and I didn’t respond, I apologize.

Honestly, thank you. I was excited to receive it.

You see, in journalism, receiving a plain brown envelope with no return address from an anonymous source is a point of distinction. It could contain leaked documents, information that exposes wrongdoings, and pieces of bigger puzzles. And somebody thinks you’re the person who could use it and bring it to light.

On the other hand, it could also contain hate message, kids’ drawings, and greetings from well-intentioned but absent-minded relatives.

But whatever the case, you never really know what to expect, what’s inside. So, it’s exciting, in a journalistic kind of way.

However, there’s a down side to this.

Several years ago, after 9-11, some terrorists started mailing plain brown envelopes containing poisonous chemical agents to elected officials.

Journalists were warned it could be a pattern, and were told to avoid opening such envelopes and call police if they received one.

And sure enough, one morning among my other mail, I found a manila envelope there, with an indistinguishable postmark, my address sloppily hand-written, and no return address.

I didn’t recognize the writing. So, I called the police. They came immediately, retrieved it and took it away. No bomb squad or anything so dramatic, just an officer with gloves.

I expected they’d open it someplace safe, and later reveal the contents to me.

I waited. A few weeks passed. Coincidentally, I bumped into the officer during a fire drill, and asked about the envelope’s contents and whereabouts.

“I don’t know what was in it,” he said. “It was sent away, destroyed.”

How deflating. But at that point, there’s nothing that could be done.

So, again, apologies if that plain brown envelope was from you, and please don’t be offended by the crack about sloppy handwriting.

But what if the envelope had indeed contained a highly toxic substance? Back then, anthrax was the poison du jour. More recently, ricin has found notoriety, most popularly in the TV series Breaking Bad, as a chemical weapon among criminals.

Unfortunately, it’s still considered a bioterrorism risk. No therapeutic antibody or vaccine is available to counteract its deadly effects.

One’s in the works, though. A federal agency called Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) has developed an antibody drug called hD9 to prevent ricin from penetrating human cells. It’s still considered a candidate drug, but it shows promise.

The key is, should this antibody pan out, how could it be economically mass produced?

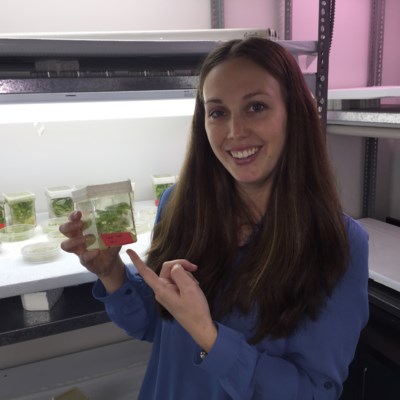

The first is of production activities in the PlantForm lab at the University of Guelph. Photo by Owen Roberts.

The first is of production activities in the PlantForm lab at the University of Guelph. Photo by Owen Roberts. The answer may be found in some unique genetically modified tobacco plants at the University of Guelph, and in a production process gaining steam by a company operating there called PlantForm.

Earlier this month, PlantForm received a $135,000 contract from DRDC to produce two grams of hD9.

That’s only about the size of a teaspoon.

But it’s enough for the agency to further study how well the antibody works.

Here it is, in a nutshell. Young tobacco plants are inoculated with antibody genes through a vacuum process, grown into mature plants in a greenhouse, then harvested. The leaves are processed in a lab, and the antibodies are extracted and purified.

Ashley Meyers, PlantForm Director of Special Projects.

Ashley Meyers, PlantForm Director of Special Projects.It’s not as simple as it sounds. PlantForm has 20 employees – a number of them University of Guelph molecular biology graduates – working to perfect the process that was developed by visionary professor emeritus Chris Hall.

They’ve made huge strides. On the civil defence side, PlantForm has also received funding from Ottawa to develop a plant-made version of an enzyme that counteracts the effects of nerve agents like sarin.

But its most exciting development is in producing quantities of what’s called a biosimilar treatment of the drug Herceptin® (trastuzumab) for breast cancer. PlantForm is trying to raise $10 million just for the first-phase human clinical study to scale up production, and prove it can viably churn out a Herceptin-like product at a fraction of the cost of the current method, which involves a fermentation system.

You might expect something so focused on human health to happen at a medical school. But like anything, it’s about people and relationships. The breadth of research at the University of Guelph, support from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs and a highly educated community gives PlantForm access to people that are the foundation of a world-class operation.

“Guelph has the expertise we need,” says PlantForm Director of Special Projects Ashley Meyers, a former student of Hall’s who’s gone on to an administrative capacity with the company. “This is a Guelph story.”