Cooks are an essential bridge between farmers and consumers, and always have been.

With creativity and resourcefulness, they turn ingredients into meals. They make raw commodities useful.

And many of them regularly turn to their cookbooks for help.

Modern cooks aren’t so tied to their kitchens. Today, about 35-40 per cent of the food dollar goes to food eaten outside the home.

But not so in the good old days. Then, most cooks (typically women) had few options other than to prepare almost everything themselves. Cooking was more than a leisurely pursuit, and cookbooks – especially those called domestic manuals -- encompassed activities in, and sometimes beyond, the kitchen.

For example, The Housewife’s Library, published in Guelph in 1883, proudly purports to be “furnishing the very best help in all the necessities, intricacies, emergencies and vexations that puzzle a housekeeper in every department of her duties in the home.”

University of Guelph food history instructor Rebecca Beausaert and student Stephanie Reynolds-Badder are pictured here with a Five Roses flour cookbook from the university's culinary arts collection. Photo by Owen Roberts for GuelphToday.

University of Guelph food history instructor Rebecca Beausaert and student Stephanie Reynolds-Badder are pictured here with a Five Roses flour cookbook from the university's culinary arts collection. Photo by Owen Roberts for GuelphToday. Such books fascinate thoroughly modern food historian and adjunct professor Dr. Rebecca Beausaert, who teaches the food history course (HIST*3240) at the University of Guelph, home of one of the most extensive special culinary arts collections in North America.

“These books give you a glimpse into Canadian society back then,” she says. “They were well used, and they shed light on the holistic role of the newly minted housewife and how she had to take so much into her own hands, not just the health and nutrition of her family.”

Beausaert’s enthusiasm for archival culinary material is shared by her class, and is soon to be experienced by the public. Over the past semester, she and her 37 students have developed a fascinating historical cookbook exhibit at the university, to commemorate Canada’s 150 anniversary. It’s called “Tried, Tested, and True: A retrospective on Canadian Cookery, 1867-1917.”

The exhibit opens ceremonially on April 7, 1 p.m., at the Summerlee Science Complex and will include talks by distinguished cookbook writers, including University of Guelph food laureate Anita Stewart.

The public is welcome, and some of the recipes from the cookbooks – all of which are part of the university’s culinary arts collection -- will be available for taste testing. The exhibit can be viewed until December 2017 in six cases on the first floor of the McLaughlin Library.

The culinary arts collection is one of seven special collections permanently archived at the university. The culinary arts collection comprises a whopping 20,000-plus cookbooks, making it one of the largest such collections in North America.

Melissa McAfee, special collections librarian, says it’s grown significantly -- by 3,000 items in two years, in fact -- and has broad appeal.

“These books are about food,” she says. “Anyone can relate to them.”

The commemorative exhibit will focus on eight themes, beginning with housekeeping in the immediate post-Confederation era, and then conclude with Canada in the midst of the First World War. Recipes in wartime cookbooks reflected the need for thriftiness; often their purpose was to help guide cooks as they worked to reduce consumption and increase production domestically, so more food would be available for the war effort abroad.

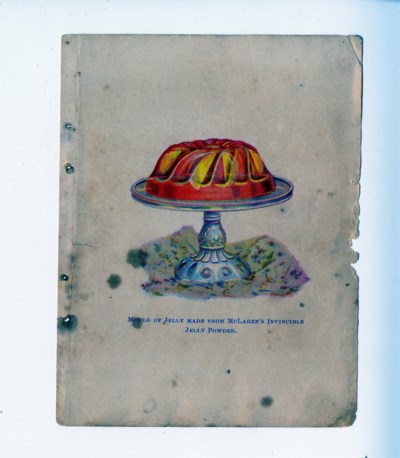

An illustration of a jelly mould, from the University of Guelph culinary arts collection. Courtesy of Rebecca Beausaert.

An illustration of a jelly mould, from the University of Guelph culinary arts collection. Courtesy of Rebecca Beausaert.Other themes including cooking in Guelph and the surrounding area, advertising cookbooks, community cookbooks, and nutrition and health explore other aspects of Canadian society, culture, and economics. The cookbooks and domestic manuals chosen to illustrate these themes were drawn from the donated collections of some of Canada’s most renown cookbook authors including food laureate Stewart, Una Abrahamson, Edna Staebler, Jean Pare and Elizabeth Baird.

Beausaert says that while the University of Guelph is an innovative leader in food and agricultural research, many people may not know the institution also has such an amazing range of resources about the history of Canadian food production and consumption.

“Many of these sources, such as the vast culinary collection, can help us better understand and learn about modern day food concerns, issues, and trends,” she says. “This exhibit is an opportunity for the public to not only see parts of this collection, but also learn about how Canadians prepared, purchased, and conserved food.”

It may sound unusual to have students so involved in helping set up this kind of exhibit. Librarian McAfee, who worked with Beausaert and her class for the commemorative exhibit, encourages faculty to have students take on assignments that require research in the archival and special collections. Such collaboration with Beausaert’s class is an example of experiential, active learning for the students.

“We want to get students face to face with the original materials,” she says. “It’s great how excited they get working with them.”